Manu Propria

My current body of work, Manu Propria (Latin for with one’s own hand), consists of soft sculptures of hands that explore the ways in which we enact personal notions of beauty, culture, and identity through micro-acts of adornment. My hope is that, when viewed in total, these sculptures present a contemporary and diverse view of feminine expression today.

My own nails have long been a source of ambivalence for me. As a child, I studied violin which required me to groom them with militaristic discipline: clean, clipped, and never extending beyond the fingertip. In early adolescence, my mother permitted me to paint my toes with the one bottle of polish she kept on her dresser — a pale, frosty pink. And it wasn’t until I was in my early 30s that I first stepped foot into a nail salon for a friend’s bachelorette party; prior to then, my sensitivities around class issues made the idea of an afternoon mani-pedi sound about as comfortable as a root canal.

Over the past few years, nails have become increasingly embraced by women (and, in some cases, men) of every race, ethnicity, and class as a canvas for personal expression. While digital ornamentation can be traced back to as early as 5000 BC when Indian women would dye their fingertips with henna (a practice that continues today) or in 600 BC when the aristocrats of China’s Chou Dynasty protected their nails with bejeweled guards fashioned from silver or gold, nail art’s current place in the mainstream owes much of its inspiration to African-American communities where black women have been experimenting with highly gilded nails for decades. On the street, on the runway, and everywhere in between, the more tricked-out the nails, the better.

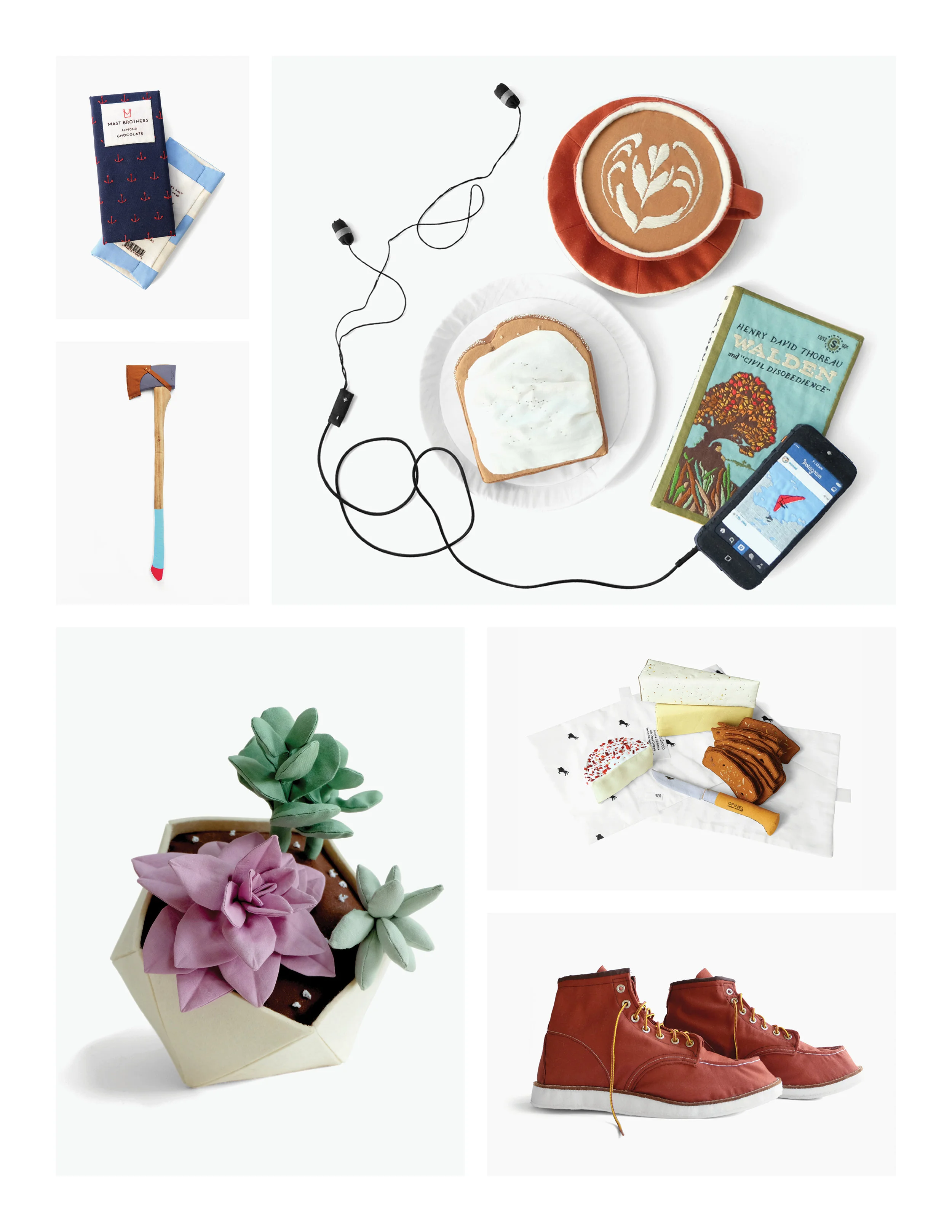

Building on construction and detailing techniques honed in earlier fiber art-based work (see Stuffed Hipster Emblems), I fashion each sculpture from materials ranging from cotton cloth to iridescent ribbon to plastic rhinestones. The firm, pliable nature of these disembodied hands is, at once, grotesque and disarming. The design of each hand is either inspired by — or a direct replica of — imagery I’ve amassed from countless Instagram and Pinterest accounts dedicated entirely to nail, henna, or tattoo art. The oversized scale (ranging from twice the size of an average hand to approximately nine feet in length) allows the viewer to appreciate the elaborate, hand-crafted nature of the miniaturized works of art created by DIYers, salon workers, and celebrity estheticians the world over.

In the wake of the 2016 US elections, I’ve experienced an even greater urgency to develop this body of work. As progressive policy impacting matters of immigration, religious freedom, equality, and reproductive rights come under siege, I’ve had the opportunity to appreciate the many ways in which visible forms of personal expression can define, differentiate, and unite us — one hijab, pink pussy hat, or nail at a time.

7 May 2017

Exhibition Proposal

Manu Propria is exhibited in a way that compels the viewer not to appraise the hands as sculptural objects worthy (or unworthy) of the proverbial pedestal, but rather, to see them as proxies for other human beings. This is achieved by encouraging the viewer to engage with the work through a series of vignettes that require a brief pause, close inspection, and a heightened awareness of his or her own body in relation to others.

When we sit, we give way to gravity. The musculoskeletal system quiets. Our gluteal muscles, quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves relax. The cerebellum — responsible for controlling balance, coordination, and fine muscle control — is momentarily freed from its responsibility of maintaining posture and equilibrium. And in social terms, one of our first welcoming acts as hosts is offering our weary guest a seat. Ultimately, the act of sitting is one that defines us as social creatures. It is an act requiring disarmament and an easing of defenses: at minimum, we feel safe enough to let down our guard; at best, we claim our place amongst friends.

The hands of Manu Propria are cast across four vignettes that suggest either social interaction or moments of silent proximity. The settings are sparsely staged, painted entirely in white, and deliberately lit to create a sense of separation between them. A few key props are used to establish neutral backdrops suggestive of context rather than fully articulated spaces. Empty seats, scattered throughout each vignette, beckon the viewer to examine the hands at close range and at “eye level”, with the hopes of cultivating a more intimate relationship between viewer and work than one achieved via a more tentative or traditional approach.

As the viewer nears the storefront, a curious sight awaits. A six foot long park bench and large wire trash can face the street. Two pairs of large hands (each measuring 36 inches in length) sit at either end of the bench with a noticeable gap between them. Debris — a discarded coffee cup, a few cigarette butts, a trampled leaflet warning of the coming rapture — is strewn about randomly on the floor.

The viewer passes by a wall bearing the title of the show and a brief written introduction. Viewers are explicitly encouraged to participate in the work by entering each vignette and claiming any available seats.

A series of large, framed photographic portraits line the interstitial space of the hallway, each depicting a person accompanied by a large pair of hands “in the wild” that conveys their considerable scale and animates them as beings: sitting side-by-side on a subway, perusing the beer selection in a bodega, or lounging on a blanket on a sunny day at the park.

Upon entering the gallery space, the viewer is greeted by a small living room setting. Its perimeter is defined by an area rug, floor lamp, and couch facing two club chairs. A coffee table sits in the center, clean save for a few half-empty glasses of wine. Pairs of large hands lounge and loaf about, with a few seats left empty so that viewers might perch.

To the right, the viewer encounters a large, roughly hewn communal table and accompanying benches. A number of oversized hands appear to converse with one another, while others rest on laptops or hold open books. Coffee mugs are scattered atop the surface, while adapters and power strips create a messy knot on the floor. A few seats remain vacant for viewers.

The rear half of the gallery is occupied by a large circle of folding chairs spanning the entire width of the gallery. The scene is both vaguely familiar and slightly uncomfortable due to its configuration, calling to mind a class discussion, church group, or AA meeting in which eye contact is unavoidable and there is nowhere to hide. Large hands are arranged on chairs: some appear stiff and upright, while others settle into a casual recline or inattentive repose. Purses hang off the backs of chairs; notebooks and tote bags are stowed beneath others. In the center of the circle, an immense pair of hands (each measuring 9 feet in length) casually rest atop one another, palm to palm. Several chairs are left unoccupied, inviting viewers to join the discussion underway.

It is my hope that by prompting the viewer to take a seat amongst inanimate hands of every color and design imaginable, from the unadorned to the expressively ornate, that he or she is granted a brief moment to contemplate the stories and experiences these hands — and by proxy, their owners — might share, if only given the opportunity.